The Lady of Roch Shan

A fairy tale with a bittersweet ending, and some confusion around its heroes and its villains

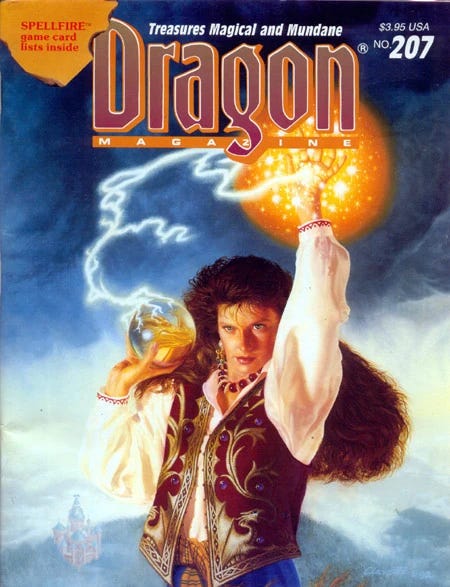

I sold this story in 1994, the summer before I went to college, to Dragon magazine. I had been subscribed to Dragon throughout my high school years: it came in a brown paper wrapper, like a porn mag, possibly because it often featured girls in chainmail bikinis on the covers.

Nevertheless I haunted my family’s mailbox, early in the month every month, for Dragon and Dungeon. Their worlds were more real to me than my own. They were a lifeline.

I submitted my early fiction relentlessly, but only to Dragon. When they turned me down, I just sat down and wrote another story.

Wolfgang Baur was Dragon’s editor-in-chief then. I’m sure he doesn’t remember me. I will always remember him, with great gratitude. I sent in story after story after story, and at first I got back form rejections. Then form rejections with a signature and a few words scribbled on the bottom—“keep submitting!”

Eventually the rejections became detailed and personalized. I was a teenager in the early 1990s: I didn’t even know what fanfiction was, but I sure was writing it. Baur told me to stop submitting Dragonlance fanfic and try something original.

So I did.

And he rejected that too, at first, but by this point we almost knew each other. “You have an ear for dialog,” he said, in yet another rejection letter. It was: no, no, no, not yet. Almost there. Keep trying. Month after month and year after year.

So I kept trying. By this point I was seventeen years old. I was despairing against the small walls of my high school experiences in Arkansas and Missouri, devouring every sci-fi and fantasy book I could find in the library, and relentlessly throwing to the editor of my favorite magazine the best I could come up with. Over and over. I needed to be part of the expansive universes that only my books—and Dragon—offered.

The worlds I glimpsed through them weren’t real, but I needed them to live.

I leaned into dialog, and narrative voice, since Baur told me I was good at that. I sent him “The Lady of Roch Shan,” a story that I wrote in a single day after spending a summer reading Yeats and John Millington Synge and several different compilations of Celtic folk tales.

And he bought it. I got to hold in my own hands the magazine that I loved so much, with my own byline in it. I have it on my bookshelf to this day. My first sale from my first editor; my first affirmation that yes, I really can do this. I can write my way into new worlds of possibility.

It meant everything. It sustained me ever after.

Later, when I became an editor myself with the responsibility of rejecting so many hopeful authors and the privilege of being able to encourage a few, I always tried to meet the same standard that Wolfgang Baur modeled for me.

Anyway, here’s that first story. It was published in Dragon #207, under my maiden name: Jo Shannon Cochran. The world reflected in this story is Celtic-flavored, but it’s fantasy. It was never supposed to be an actual historical setting—it’s not authentically Scottish, or Irish, even though it’s obviously Gaelic-flavored and very much reflects the reading I was doing at the time. And the kind of writing I would keep on doing.

It’s a fairy tale. It’s got a bittersweet ending, and it’s not quite clear who’s meant to be the hero and who the villain.

It turns out I write those sorts of stories over and over. But this one was first.

I know a good position when I see one, which doesn't explain how I ended up with Laird Rheagel of Roch Shan, he so tight with the Church and all. Indeed I was surprised that he accepted me. Not that I consider myself impious, mind you. I say the chants regularly and properly, and I wear the Sign.

Actually, I am familiar with many signs, which is the entire problem itself. These young priests are so uppity. Their knowledge can't simply be best, but it must be only—and whoosh! a thousand years of learning dumped out the window with the bath water.

But I say a girl has to be careful, especially when she's seen as many winters as I have and is no longer often called a girl. So I try to keep on the good side of all the heavens, although some are more easily satisfied than others. I won't say I was driven out of my previous home, but when the eggs are rotten, I don't stay for the omelet: and when the local priest denounced me as a witch, I left.

Although as far as that goes, he was right.

I have the herb-lore and the star-knowledge, like many a country woman, although I fancy I'm wiser than most in those ways. And there's more in me than weed-cures and old wives' tales, too, not that old wives are anything to discount. No, I'd sooner offend a priest than a wise old wife. It's the choice between risky and worse.

But what I am telling you is, I have a touch of the canny.

So, Roch Shan I mentioned. It's a hard strip of land between the mountains and the sea, and hard are its people and hard is its lord. A pillar of the Church, he is, and I expected no help from him when I came in. But he said he might have a bit of washing to be done, and he offered me a decent living wage, enough to put honey in the tea.

Very surprising, in that they say he's been known to geld an ant and make the meat do for a month.

Anyhow, that's the way I became washer-woman for the laird of Roch Shan. It wasn't many years later that he brought in a wife, a young lady from foreign parts. I turned out to see her ridden in, all in silk and crushed velvet, atop a high-stepping white mare. She was pretty enough, if a bit thin and nervy-looking, but it wasn't the thinness that caught me: it was the wildness in her dark eyes and the way she seemed to move through shadows never cast by earthly light.

And I said to myself, she's got it.

When the ceremony was over and things had calmed down, and she'd taken up plain clothes and plainer duties, I contrived to come up beside her and say a few words in quiet. Everything I mentioned was double-hidden, but recognizable to anyone with fey knowledge. She treated me quite polite but seemed confused, and it was obvious she'd had no training.

So I thought it would be all right. A mistake, as it turned out, and as I freely admit.

But what have I to do with high-born ladies? I did the washing. I kept to my cottage. Her ladyship grew thinner and paler, even her hair turning an ashen sort of color, but her eyes stayed dark and mad.

It was the next autumn that the laird came to my cottage. Unseasonable frosts had killed most of the late harvests, and the nights were filling with mist. It was through one such fog that he came riding, alone. I heard the hoofbeats before the shrouded light of his lantern came into view. I watched through the slats of the window-shutters as he swung off the horse and strode to my little door.

He struck it three times, hard, and I drew back the bolt and let him in.

Laird Rheagel is a craggy man, heavyset, with pronounced features and a bony nose. A face with character, as they say, and beauty isn't everything. There was something in his expression made me forego the usual scraping; mutely I offered him a chair. It's the only one in the house, so I stood before him.

"My lady Elin is sickening," he said without preamble.

"The night air seems to be doing her harm. Each evening she slips away. I know this, though I cannot prove it, for she has eluded every guard I set upon her, and when I watch her myself I fare no better. Each morning she returns, further weakened. When I suggested she forego her nightly outings, she spoke these words in reply: 'Hold the sunbeam, hold the sea, chain the zephyr, but do not chain me.'"

He was quiet a moment, watching me closely. I caught myself bunching and unbunching my skirts in my hand, and forced myself to be still. But it was a nice jam!

If I did not help him, I would lose my place in Roch Shan, and stars know there's not much further down to go from there. But if I did what I could for him and his lady wife—and that knot would take some untangling—I'd put myself square on the wrong side of the Church again. It was meddling in these matters that nearly ruined me before.

"I don't know that I'd be all that much help to you, Laird," I told him, though I had faint hope of excusing myself so easily. "I'm but a simple woman, far from blood and breeding..."

"We are all more than we appear," he said. That earned him a sharp look; he was certainly more than the devout son of the Church he played to. Not so funny, after all, that spot of washing that showed up so timely-like.

"Listen," he said, leaning forward, his eyes boring into mine. "There is much here at stake—Elin is sick, and winter comes early."

That reference took me a moment to catch, as I stared back at Rheagel and thought that he was as grim as his land...

…and then I understood. It's seldom, now, that any of the ancient links between land and ruler are preserved, and more seldom still that the nobles understand them. But in fierce and forsaken Roch Shan, they would long be kept alive.

There was suddenly little choice to the matter. "I'll do what I can," I said unhappily, "though you might be wishing otherwise when it's seen through. I don't guarantee success, nor rosy endings. And I can't work alone. It's a strange affair, and I'll need some strange sorts of help."

He nodded and stood. "My resources are at your disposal."

"Then I'll be at the manor tomorrow night; I've things to gather here." He nodded again. "Good night, sir," I said.

"Good night, mistress," he replied, and left, stooping a little to clear the lintel.

I didn't shut my eyes that night. I packed up a bag with clothes and toiletries, then spent the rest of the night dragging out all my old books.

I have the letters, though I am not quick with them, and by the time I finished my eyes were as puckered as raisins. My mind also was sore, from too many thoughts about the lady and her situation. Especially her rhyme—that was important, as Rheagel seemed to understand. Uncommon wise of him to pick it out like that to tell me. He has none of the eldritch abilities himself, but my best wager is that his mother was artful that way.

Since I wasn't certain what I was looking for, it was difficult to find, but by morning I held enough information to be satisfied. Then I slept. In the afternoon I woke, and traveled to the manor to be presented to Lady Elin.

She looked worse up close—or she had deteriorated since I saw her last. Her skin was all stretched out over her fine bones, and her bruised eyes darted ceaselessly around the room. Jumpy as a grasshopper she looked, and about as strong. She smiled thinly and greeted me.

"Good mistress, I welcome your company," she said with no hint of irony, though she surely knew I was her jailer and not her companion. "Such a fine day for pleasant conversation."

"As lovely as you are, my lady," I said, curtsying, "though it seems to have wearied you. You look tired."

"Truly?" she asked. "It must be the afternoon sun, so harsh on the skin. Do you know any way to defend against it, other than a veil?"

And so we discussed the benefits of red dock and of balsam root, and for each of my sharp questions she had a deft evasion. Grasshopper I called her, but she was closer to an eel.

As evening approached, she suggested it was time for bed. I agreed, though I had no intention of sleep. She began to unbraid her fair hair. As she did so she hummed a low tune, or perhaps sang it under her breath. It seemed to have words, but I could not make them out. As I listened, a drowsiness came over me, and a darkness seeped around the edges of my vision, until only Elin was clear. I watched as she finished brushing out her hair and went to the bed, but did not climb in. Instead she knelt and reached beneath it, drawing out a pair of sturdy boots. Then she turned straight to me, giving me a very level look, and the darkness closed in.

When I woke up, of course, it was daylight. I didn't need a kettle for my tea that morning; I could have brought the water to a boil just cupped in my hands, I was that angry. But soon it turned to befuddlement. I was sure the girl had known no witchery when she came to Roch Shan. Where had she learned it so quickly? I looked at the bed and there she was, sleeping like a child.

I went to the laird. He rose to greet me, with a question on his face.

"This is what I need," I told him, "to hold the sunbeam: a golden chalice filled with the clearest water in your land."

"You shall have it," he said.

The chalice was easily procured, but the water was more difficult; even the water in Roch Shan is muddy. When it was in my hands, I took it back to the lady's rooms for another afternoon of elusive conversation. I set the chalice on a western windowsill.

"So quickly time passes," remarked the lady as it grew late. "It is time for bed again."

As she took down her hair, I moved to the chalice, where the last light of the setting sun was reflected in dancing lights on the surface of the water. I leaned down and set my lips to the water just as Elin began her spell. I felt the drowsiness, but the shock of cold water in my throat washed it away, and the reflected sun kept my vision bright.

I drank the last sip of water just as the sun disappeared completely and Elin finished her song. I sank to the floor and pretended sleep, until I heard her soft tread leave the room, and the door swing closed behind her. Then quick as I could, I was up and after her.

She walked silently down the hall and into the servant's wing, out a side door, and into the night countryside. She picked up speed as she moved farther from the manor. I had all could do with following her. There was no way to stay hidden, but she never once looked back.

I had not had time to catch any sort of shawl, and I was mightily cold. She wore only a thin shift but was seemingly not bothered.

I began to worry about the terrain we were crossing. Some of it was familiar and some of it was half-familiar and some of it was altogether strange, though I had made extensive explorations of the area. We waded through a little stream, which I recognized, but the wetting of my feet did nothing to improve my chill.

Then we came to another stream, a deal wider than the first, and with no call to be there. Except for the size, it looked exactly like the one we had already crossed. Lady Elin strode through it as easily as she had the first, the water barely skimming her white ankles. But by the time I struggled through it, I was wet to the waist.

I ran to catch up with Elin, only to find her at the bank of a third river, this one three stones' throws wide. No such water exists in Roch Shan.

She stepped in, her feet making no ripples in the river's glassy surface. As before, she walked easily, never sinking below ankle depth. As I followed, the water deepened. I was in it to my neck before I had gone a quarter of the distance. I was not born with flippers; I cannot swim. So I stood and watched her step lightly through the water until she was completely taken by the night.

Then I made my way back, which was somehow a far longer journey than the coming had been. It was late morning when I arrived, footsore and muddy from head to toe, at the manor doors. Her ladyship was in bed and sound asleep.

"This is what I need," I told Laird Rheagel, "to hold the sea: one moonstone, ground fine."

"You shall have it," he said.

That evening I used the chalice to feign sleep, as before, and at night slipped out after the wandering lady. Also as before, I had no wrap. It wasn't enough that the Lady Elin was bound and determined to kill herself. No, she would have me catch my death as well. Wherever she had inherited her fey blood from, it had come with no sense. The Sight will never substitute for what any fool can see.

Then I was at the third river, the still black water. Elin made her usual careless crossing. I waited until she was gone from sight, then drew out the moonstone packet Laird Rheagel had given me. I took the tiniest pinch of the powder and sprinkled it on the water.

Like the tides responding to the call of the moon, the river receded, parting on either side to make me a path. I walked forward, tossing a bee's thimbleful of moon dust ahead of me with every step.

When I came at last to the other side, I found myself in a country I had never seen at all. I stood at the foot of a high hill, black against the gray sky. The warm winds of late spring curled around me and ruffled the grasses. I glanced at the sky: as I had expected, the constellations had shifted. The Hunter, the Maiden, the Beast—they were gone. In their place shone the Crown, the Hand, the Tree—elven figures all.

I was shaking like a dry leaf. Oh yes, I was scared—this land was none to trespass in—but I was joyful too, in a fierce way. No feeblebrained witch-hunter could have followed the path I had navigated.

I put a foot on the hilly slope, gathered my sodden skirts, and began to climb. I was out of breath by the time I reached the crest, and I paused to rest. A good thing, for in the silence I caught the faint sound of voices. I crept forward and saw figures standing at the base of the next hill. Behind them, leading into the side of the hill, was a small opening. It spilled enough light to clearly illuminate one of the two figures: Lady Elin.

"No," she was saying, "no danger—none there has the skill to break the charm you gave me."

"Are you ready, then?" the other spoke. It was a man's voice, rich and musical. He was silhouetted against the bright opening, standing just inside the hill, and I could not see his face. But no mortal was ever built so tall and lithe.

"I am ready," she said. The elven man reached a hand to her, and she stepped forward as if to take it. But although he moved not, all her reaching brought her only a hair's breadth from him, no closer. She cried out, a wail of sorrow and frustration.

"One more night," he said, dropping his hand. "One more night and the strong slow spells will be finally bound; the pattern will be entire; the crossing will be complete."

She made a reply, but I could not hear it—the wind had picked up. By the end of the elf's words, it was the force of a strong storm, whipping my hair across my face. As I watched the two, I saw that he was drifting away, or we were. In any case, the winds were blowing a wide rift of black water between us.

Before Elin could come on me, I turned and picked my way back down the hill and through the water, across the streams and to the manor doors. The lady never overtook me, but still she was there by the time I returned.

I went to Laird Rheagel. "This is what I need," I told him, "to chain the zephyr and your lady: one eagle's wing—and it will be the last thing I'm needing, for success or failure, tonight this ends."

"You shall have it," he said, "but mistress, bring me success."

I didn't bother joining Lady Elin at all that afternoon; I caught up on some much-needed sleep and went to her at sundown. She didn't look like she'd even noticed my presence or the lack of it. She was ashen white except for her cheeks, which were flushed blood red, and her eyes, which were feverishly bright. She was burning herself up from the inside.

With the sunlit water I resisted her song of sleep, and followed her out into the night. This time I didn't notice the cold: my fear was hot inside me.

I kept close behind Elin as we crossed the three rivers and came again to the twilight shore. Her pace quickened as we topped the high hill. On the next slope stood the elven doorway, and a man was waiting.

I began to run then, as fast as I could, nearly tripping over my sodden skirts, but I caught her at the foot of the hill. She whirled to face me, her eyes lit with panic.

"Oh no," she whispered, her face crumpling, and then shouted out, "no, oh no no no!" She struggled like a wild thing, but she was very weak, and I held her easily.

"Lady," I said with pity, "you cannot make this crossing. It is killing you."

"It is the other world that is killing me," she cried passionately, "never this one. All my blood has called me here. Witch that you are, woman of wisdom, can you not see that this is my only chance at life?"

"You are no changeling," I told her. "You are an untaught sorceress, caught up in magic that far exceeds you. And you have duties, sacred bonds...Lady that you are, life of the land, how can you forsake Roch Shan?"

"Roch Shan!" she laughed derisively. Her laugh was high and brittle, a sound like clattering glass. "Roch Shan is dead already!" She abruptly ceased fighting and collapsed at my feet. "Please," she said hoarsely. Her voice tore from the back of her throat, formed not from sound but from the pure emotion of desperation. "Please!"

I felt for her, for she was doomed. She had walked the elven lands, and there would be something in her forever caught there. But however she denied it, Roch Shan was a part of her, and her soul would dissolve before those bonds did.

I looked up, glancing at the elf before us. He had made no move during the whole struggle. He stood just inside the passage leading into the hill, framed in light, watching. He met my eyes.

He was clad in what seemed to be diamond-studded silk, dark blue or perhaps purple. He wore a silver circlet. His hair was night-black, catching the light from the doorway in a reflective blaze, and his eyes were starry bright. He had a bittersweet face, perfectly formed, with no human blemish to give the eye a respite. He smiled at me, a dark invitation. I trembled.

Elin, at my feet, reached up to clutch my elbow and bring my attention back to herself. She spared no glance for the elven lord. I wondered suddenly if she understood this land any less shallowly than she did Roch Shan. The elf's eyes were upon me, and I wondered further whom he had opened his borders for.

I fumbled under my belt and found the eagle's wing. As I withdrew it, Elin's eye fell upon it and she lunged upward, but her assault was frantic and clumsy. I evaded her and flung the wing to the ground.

Immediately the winds flared up, reaching gale force within seconds. The elven hill began to recede. The winds tangled my skirts around my legs and tore away Elin's howls of protest. The light from the hill disappeared into darkness; the wind died. Elin was silent.

I touched Lady Elin's shoulder gently and turned her about. She made no resistance, but followed me dumbly. The wide river was gone; we stood at the bank of the one small stream.

It was dawn when we reached the manor. Laird Rheagel was waiting for us. I drew Lady Elin into the hall, where she stood, white and silent, before the laird. She seemed to be looking at some point over her shoulder. Every line of her body was one of despair.

"The spell is broken," I said. "Roch Shan should recover now. But you will be wanting to put bars of cold iron across all of your windows and all of your doors."

Rheagel nodded. "Will she recover?" he asked, with an undertone to his voice that made me look more intently at him and notice the way he was gazing at his wife, as if her pain was his. But she stood like a dead thing and was not heeding.

From all I knew of similar cases, the truth was that she would probably not last out the week. I hesitated, watching them and the way they stood, and I hated to say it. Perhaps there was something more there to change the accounting: his will, maybe, and hers too, and not least that of this stubborn realm.

Roch Shan is a grim, grudging land. But it is wild and proud, and there might be strength enough in Lady Elin to someday come to love that.

"In time," I said, "in much time...she may forgive."

He nodded, accepting what I had said and what I had not, and led the lady away. I went back to my cottage, to sleep for a week.

Then I began taking stock of all my possessions. Astonishing how quickly they multiply, those useless little bric-a-bracs. You'd think they breed. It took me days and days to sort them all out and pack them up.

It's not that the laird was ungenerous. He offered me handsome compensation and a permanent position at the manor. But I refused. You see, I have been remembering the elven lord's smile, wondering if they have any washing to be done there beneath the Hollow Hills—and I know a good position when I see one, yes I do.

(art by Arthur Rackham, from the illustrations to The Rhinegold and The Valkyrie, 1910)

All of my Monday speculative fiction newsletters are free. But if you want to support my work, the absolute most valuable thing to an indie writer is word-of-mouth. It’s free to leave an Amazon review, to forward a story you liked to a friend, or to post about it on social media.

Or you can subscribe! I can’t set prices lower than $5 a month, which honestly seems high to me, but for annual subscriptions I’m allowed to go as low as $30. Two fifty a month for four weeks of stories is closer to reasonable, right?

Or for $2.99, you could buy a book! Anyway, thanks for reading. Next Monday I’ll share “The Fairy Midwife,” a contemporary urban fantasy story that first appeared in the anthology Fae from World Weaver Press.